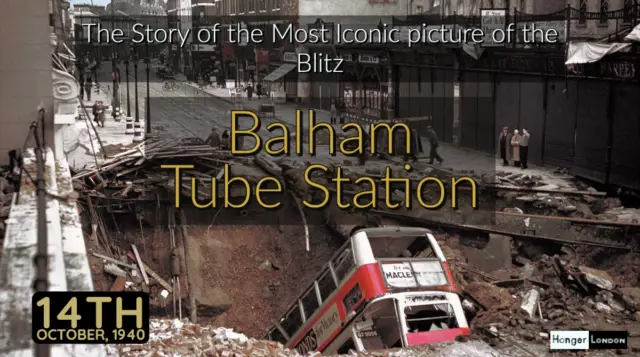

Over eighty years ago, on October 14, 1940, in the South London area of Balham, a devastating bombing raid produced one of the stand-out pictures of the blitz, with a photograph of the number 88 London Bus, on the last run of the day, sunk in the bomb crater above the Balham tube station.

The bomb, weighing 1,400kg, struck near United Dairies on Balham High Road at 8:02 pm, causing catastrophic destruction. This event took a particularly tragic turn when a double-decker bus driving past fell into the crater and ruptured a water pipe, leading to the drowning of numerous individuals who were seeking shelter in the Balham underground station below. The death toll was estimated at 66, and it’s noteworthy that it was the bus’s impact and subsequent flooding that caused most of the fatalities.

A London Transport staff member happened to be sheltering on the platform with his family, with an intimate knowledge of the station’s intricate tunnel network, led scores of individuals to safety, offering a glimmer of hope amidst the chaos. Without his heroic efforts, the death toll could have been much higher, as up to 500 persons could shelter in the underground station.

The aftermath of the Balham bombing took an additional two months to recover the last of the bodies, the station’s resilience and determination were showcased as it emerged fully functional once again by January 1941. This swift recovery, against all odds, underscored the unwavering spirit and determination of both the Balham community and London as a whole.

The Youngest and Oldest Victims of the Balham Bombing

The sombre roster of lives forever altered by the Balham bombing comprises heart-wrenching stories that encapsulate both the fragility and resilience of humanity. Among those who perished, the Brown family of Hillingdon Street found themselves tragically entwined in the events of that fateful night. Within their fold, Constance, a vibrant soul of 14, and her younger sister Joyce, aged 12, were swept away by the devastating tide of war’s indiscriminate fury. Their lives, brimming with youthful promise, were abruptly extinguished, leaving an indelible void in the hearts of those who knew them.

Yet, amidst the heartache, the innocence of childhood was further shadowed by the loss of two tender souls. Michael Ravening, a mere 4 years old, nestled in the embrace of his mother Elsie, aged 35. Their bond, nurtured through shared laughter and whispered dreams, was tragically severed by the merciless hand of war. Little Michael’s cherubic smile and Elsie’s nurturing warmth became poignant reminders of lives cut short and futures forever altered.

Similarly, the tragedy reached across generations, casting a pall over families who had weathered the trials of life together. Arthur George Sexton, just 4 years old, found himself ensnared in the same fate as his parents, Alfred and Maud. At 46 and 34 years of age respectively, this couple had likely weathered many storms together, only to meet their untimely end in the wake of a bomb’s destruction. Their intertwined journey, marked by shared laughter and shared sorrows, came to an abrupt and tragic conclusion.

In a striking contrast, the saga of loss extended to the other end of life’s spectrum. Roy John Dibble, a venerable soul of 97 years, stood as a testament to the passage of time and the depths of human experience. A resident of Tate Street, Lambeth, his years were etched with tales of a bygone era, a living chronicle of history that spanned nearly a century. His presence at the epicentre of this tragedy underscored the indiscriminate reach of war, a stark reminder that age and wisdom could offer no protection against the forces of destruction.

These poignant narratives, meticulously preserved by the vigilant efforts of the Wandsworth Heritage Service at Battersea Library, and catalogued within the records of the Home Guard, illuminate the diverse tapestry of lives forever linked by the Balham bombing. Each name, each story, becomes a poignant thread in the fabric of remembrance, a solemn tribute to the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity.

The Most Iconic Blitz Picture of World War 2, the Balham Tube Station Bomb

The underground network served as an air-raid shelter during World War 2. Balham Tube station was one of the stations on the network that was deep. Just past 22:00 on the 14th of October 1940, a 1400kg fragmentation bomb fell on the road which blew a huge crater. The number 88 London Bus, driving in the blackout, subsequently fell into this whole, and no one on the bus was killed. The image became one of the most iconic images of the London Blitz. Read more of the untold story

The Image is Linked here: source https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/balham-tube-station-german-air-raid-1940/

‘Walk the Barratt Way’ – life in the Balham Blitz Picture

The slogan “Walk the Barratt Way” is more than just a catchy phrase – it represents the core values and principles that have made Barratt Shoes a very successful manufacturer of lavish footwear in the United Kingdom and Ireland footwear markets. At the time of this picture, the brand was being sold in over 100 retailers across the country, with a reputation for its high-quality boot catalogue with high-quality illustrations. The manufacturer ran the national slogan, ‘Walk the Barratt Way’ and was based in a spectacular neo-baroque factory in Northampton. The end shop in the photograph is a Barratts store, along with its bus-size slogan on the side of the building.

The company would go on post-war to grow to over 400 retail outlets with several other shoe manufacturers joining the group. Unfortunately, the company went into administration and closed in 2013.

Dunn & Co Hats – life in the Balham Blitz Picture

During World War II, Dunn & Co. was a well-known British manufacturer of high-quality hats for men. Their hats were worn by military personnel and civilians alike, and they were known for their durability and style. In this blog post, we’ll take a closer look at Dunn & Co. hats and their significance during World War II.

Dunn & Co. was founded in 1889 by Robert Henry Dunn, and by the early 1900s, the company had become one of the most respected hat makers in the United Kingdom. They were particularly known for their high-quality tweed hats, which were popular with hunters and other outdoor enthusiasts. During World War I, Dunn & Co. provided hats to the military, and they continued to do so during World War II.

One of the most iconic Dunn & Co hats of the era was the service dress cap, which was worn by officers in the British Army, Royal Navy, and Royal Air Force. The cap had a distinctive shape, with a peaked front and a band around the base. It was usually made of lightweight material, such as khaki-coloured tropical wool, and it featured a leather chin strap and brass buttons with the wearer’s rank insignia.

Dunn & Co also produced a range of other military hats, including the beret, which was worn by soldiers in the British Army’s Parachute Regiment, and the field service cap, which was worn by soldiers in the Royal Army Medical Corps. These hats were made to the same high standards as the service dress cap, and they were prized by military personnel for their durability and comfort.

Outside of the military, Dunn & Co hats were also popular with civilians, who appreciated their classic style and excellent craftsmanship. During World War II, many men wore hats as a matter of course, and Dunn & Co was one of the most respected makers of men’s hats in the United Kingdom. The company’s hats could be seen on the heads of everyone from business executives to factory workers.

Today, Dunn & Co hats from the World War II era are highly prized by collectors and vintage enthusiasts. They are a tangible reminder of a time when men took pride in their appearance, and when the quality of one’s clothing was seen as a reflection of one’s character. While the world may have changed since the 1940s, the timeless appeal of a well-made Dunn & Co hat endures.

Sheltering in the London Underground during the Blitz

At the beginning of the war, the government decided to keep the underground network locked after the last trains, a decision based on the assumption the network should be kept clear and operable for the London working economy and for the free flow of the military if required. There was also a view, not dissimilar to Jules Vern’s 1886 novel, Clippers of the Sky, which made stark predictions of aerial bombardment on civilian populations in heavily populated areas. A view that considered the opening of the underground for Londoners to shelter in, would somehow promote a subterranean civilian population, that lived prefer to reside in the shadows, below the ground, and wouldn’t come out.

The problem with what the government may think is the right thing to do often in so many times conflicts with what the population demands and it often leads to people having the power to move the agenda, sheltering on the underground was such a thing that locals began sheltering in the tunnels of the underground even while the trains were still running. In fact, passengers and shelters co-existed, and the network continued to operate to schedule the local populations using 79 Tube stations for shelter.

Water Flooding on the Northern Line during the Blitz

The Balham direct hit was to show that nowhere was really safe during the London Blitz, even though the station was one of the deep stations on the network, at 26 meters below sea level, the armoured piercing bomb that landed in the road above collapsed the roof of the connecting underground tunnels, breaking the main water pipe, sewage pipe, and gas pipes.

The lights went out and the waters began to fill the platform area. It was said floodwaters were within reach of the Clapham South station, which was some 3/4 of a mile up the road.

Surviving the initial bomb explosion, what caused most fatalities at Balham?

The Balham bomb triggered a chain reaction of events that combined to seal the fate of some of the estimated 600 people who were sheltering in the station. The lights went out, and the tunnel roof lining connecting the north and south tracks collapsed. With no lighting, the tunnel went into total darkness, and without any light, you could not even see your own hand in front of your face. The 1400 Kg Armoured Piercing Bomb blew a large hole in the middle of Balham High Road, right above the Balham station complex.

The number 88 bus, on its last run of the day, driving in the blackout, did not see the large bomb crater in the road and crashed straight into it shattering the main water pipes. The water now started to flood down the tunnel network below. The station was fitted with watertight doors with the working assumption floodwaters would come from street level. The passengers on the 88 bus were helped to safety by climbing a lowered ladder from the back of the bus to the road.

You can now imagine, with the noise, smell, and rising waters panic setting in the amount of falling debris, gravel, and ballast the bomb caused, the rising waters from the broken water and sewage pipes, and the stampede to get out cause the most fatalities of the Balham Bomb disaster.

Closing thoughts, the strength of the community

The Balham Bomb was just one of many devastating attacks that London suffered during the Blitz, but it was a particularly poignant reminder of the horrors of war. The tragedy of the Balham Bomb serves as a reminder of the importance of community in times of crisis, and the strength that can be found in coming together in the face of adversity.

Today, the Balham underground station still stands as a testament to the resilience of the community that rebuilt it after the devastating attack. The station has been renovated and restored, but the memory of the Balham Bomb remains an important part of the history of the area and a reminder of the sacrifices made by those who lived through the Blitz.

Where is Balham

Balham nestled between four distinctive south London commons, was thrust into turmoil during the Blitz. Balham’s geographical position placed it between the lush expanse of Clapham Common to the north, the verdant tapestry of Wandsworth Common to the west, the serene charm of Tooting Graveney Common to the south, and the intimate embrace of Tooting Bec Common to the east – the latter two, historically separate regions, are often referred to as Tooting Common by locals and Wandsworth Council.

Balham, London Borough of Wandsworth, England, United Kingdom